Theologian Marcella Althaus - Reid died February 20th 2009, after a theological journey that began with the study and practice of liberation theology in the slums of Argentina under the military junta, and ended as Professor of Contextual Theology at Edinburgh University, where her interests included Liberation Theology, Feminist theology and Queer Theology. I have an instinctive personal response to this trajectory - my own journey in faith was strongly coloured by my experience of the Catholic Church under apartheid South Africa as an important force campaigning for justice and peace. As in Argentian, liberation theology was an important influence in the South African Catholic Church, where it transformed into Black theology - and later contextual theology. Like Althaus- Reid, my conviction that Christianity must stand on the side of justice and inclusion for the marginalized has led me to a conviction that this must also include justice in the church, and justice also for the sexually marginalized of all shades: gay, lesbian, trans, bi- or simply queer (in either meaning - sexually non-conformist, or just "strange"). And like her, I too have migrated from a land of southern sun to British damp and cold. So - I could be biased.

As a theologian, her work was undoubtedly influential - but also highly controversial. Just the titles of her two major books illustrate this: "Indecent Theology", and "The Queer God". I love the title and concept "Indecent Theology" (which I have not read), which suggests for me two distinct concepts: that theology should not shrink from tackling concepts that are too often avoided as "indecent", and simultaneously that in tackling conventional themes, it need not automatically adopt a reverential, deferential submission to received, supposedly authoritative opinion. Her thorough grounding in liberation theology left Althaus - Reid with a firm commitment to the value of base communities, in which ordinary people in small groups can do theology by talking about the influence and impact of God in their lives, in their unique circumstances. The formal, accredited theologians have greater training and academic understanding of the theory of God - but the base communities have real - world experience of their own lives. Both methods of doing theology deserve attention and respect.

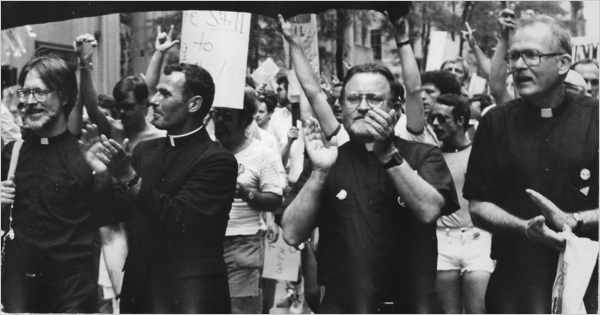

For her admirers, she was a pioneer in the transformation of gay liberation theology into queer theology. See for instance, Jay Emerson Johnson of the Pacific School of Religion, in a commemorative reflection after her death:

Hardly anyone has a neutral reaction to the word “queer.” People either love it or hate it. I used to belong to that latter camp until a wiry, effervescent, brilliant Latin American liberation theologian converted me. That theologian’s name was Marcella Althaus-Reid, who passed away on February 20 – far too young and with many more theological and spiritual insights left to offer to a world that desperately needs them.

“Queer theology” has been bubbling up in some quarters for a while now, but not quite as long as “queer theory.” Both spark considerable controversy, and sometimes for similar reasons. Usually the word “queer” is enough to send an otherwise congenial dinner party of LGBT people rocking with impassioned disclaimers, hurled history lessons, and proffered pleas for tolerance. In religious circles, gay and lesbian people have been working for decades to carve out a “place at the table” in faith communities that they so rightly deserve. The work can be slow and arduous, which the word “queer” – some strenuously insist – can derail. A few years ago I attended a national gathering of LGBT-affirming ministries where a well-known gay Christian author practically begged his audience of several hundred to refrain from using “that word” in their advocacy work. It simply perpetuates the assumption that we’re different, he explained.

That’s exactly the point, as Marcella Althaus-Reid would have chimed in had she been there. We are different. And the only way to do Christian theology is from that place of difference. The “we” for Althaus-Reid didn’t mean only lesbian and gay people, nor the ones so quickly added on later, like bisexuals and transgender folks. “We” are all those who don’t fit the regulatory regimes of both state and church marked by gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, class, and economics. For her, “queer” maps out a space of resistance to those regimes, not just to oppose but creatively to construct, re-imagine, and envision a different kind of world.

Johnson doesn't spell it out, but her understanding of "queer" was emphatically not restricted to lesbian, gay and trans - it very much included bisexual (which she was herself), and all the varieties of sexual non-conformity - she was one of the few queer theologians to include discussion of S/M sexuality.

For her detractors, there are many counterarguments. A good friend, who knows far more about the Catholic Church and theology than I do, once described her to me quite simply as a "nutter". Her writing has far more the character of post-modern philosophy or literary criticism than of conventional theology. Her sources are secular writing more often than they are scriptural, or based on earlier theologians. (When I read "The Queer God", I was baffled at times by the style and the dense, sometime impenetrable writing - but equally stimulated and excited by other passages of brilliance and insight). Some would even argue that her theology is post-Christian, not Christian. For example, Rollan McCleary:

In reality, Marcella Althaus-Reid constitutes one of the strangest phenomena in the long and diverse history of Christian thought. To judge from her published works this lecturer in “Christian ethics” who dismissed the Ten Commandments as “a consensus” reflecting “elite perspectives” (2003:163) was less a spokesperson for the “indecent” or disruptive she is supposed to represent and that might have had it uses, than an unusual kind of atheist and blasphemer whose written wit and reportedly frequent laughter in person barely disguised the extent of the game she must have known she was playing. Within the increasingly effete, too often irrelevant world of theological and Queer studies she found opportunity. Her admirers, and in her last years she had them on an international scale, have been deceived or perhaps never really understood what she wrote - whole chunks of it admitted to be dense, difficult, interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary based. Those who truly understood might have to be considered infidels towards the religion they profess.

But even her detractors agree on some undeniable lasting value in her work. McCleary concedes in his post,

.... even if Marcella hadn’t returned right answers she had raised pertinent questions based on experiences not to be ignored.